It was the best of times and the worst of times for Green Arrow in the 1980s. Entering his fourth decade of his publication history, he was still yet to see his own solo title. Firmly established as the radical left-wing voice of the DC Comics universe, the late 1970s saw him slightly more domesticated and focusing on his own life away from the Justice League with Black Canary.

It was the best of times and the worst of times for Green Arrow in the 1980s. Entering his fourth decade of his publication history, he was still yet to see his own solo title. Firmly established as the radical left-wing voice of the DC Comics universe, the late 1970s saw him slightly more domesticated and focusing on his own life away from the Justice League with Black Canary.

After extended runs in Action Comics and World’s Finest Comics, covered in Part 2 of this series, the 1980s would finally see Green Arrow get an ongoing book, although it would take at least two tentative mini-series to get there.

In this third part of our travels through the history of Green Arrow, we’ll sleuth through Detective Comics, see takes on Green Arrow by both Alan Moore and Frank Miller and go a little deeper with the often overlooked 1983 Green Arrow mini-series, and witness the first “death” of Green Arrow!

Also read:

- The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 2 – Hard Travelling Through the Wilderness Years (1970 to 1979)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 4 – Longbow Hunting Through the Wonder Years (1987 – 1993)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 5 – At the Crossroads of Death with Connor Hawke (1994 – 2000)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 6 – Quiver through Brightest Day (2001 – 2011)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 7 – Losing the Beard: The New 52, ‘Arrow’ and the Contemporary Age (2011– )

The Road to Solo: Leaving the League, Detective Comics and Alan Moore

As the 1980s began, Green Arrow was no longer co-leading a title with Green Lantern, but he continued to distance himself from the rest of the Justice League. In “Testing of a Hero!” (Justice League of America #173, December 1979), Oliver Queen sponsors Black Lightning to join the League. “He’s just what we need, troops,” he argues. “Cool, smart – and black!” After being accused of tokenism, The Flash levels an accusation that was hard to ignore: “I think your judgment is warped! You’re trying so hard to be Mister Liberal – you don’t think straight anymore!” In the following issue, Arrow accuses the League of messing with Black Lightning’s test to enter the JLA. These confrontations and Ollie’s “different way of looking at things” ultimate leads him to quit the Justice League in issue #181 (August, 1980), in a chapter by Gerry Conway entitled “The Stellar Crimes of the Star-Tsar!”.

As the 1980s began, Green Arrow was no longer co-leading a title with Green Lantern, but he continued to distance himself from the rest of the Justice League. In “Testing of a Hero!” (Justice League of America #173, December 1979), Oliver Queen sponsors Black Lightning to join the League. “He’s just what we need, troops,” he argues. “Cool, smart – and black!” After being accused of tokenism, The Flash levels an accusation that was hard to ignore: “I think your judgment is warped! You’re trying so hard to be Mister Liberal – you don’t think straight anymore!” In the following issue, Arrow accuses the League of messing with Black Lightning’s test to enter the JLA. These confrontations and Ollie’s “different way of looking at things” ultimate leads him to quit the Justice League in issue #181 (August, 1980), in a chapter by Gerry Conway entitled “The Stellar Crimes of the Star-Tsar!”.

Here we see a character that began to emerge all the way back in Justice League of America #66 under Denny O’Neil, filtered through the radical “relevant” comics of the 1970s and no longer part of the chest-logo-puffy-shirt crowd. By the end of the decade, Mike Grell would have him living in complete isolation from the rest of the DCU, but during this period it was enough to segue him into more of an urban setting that would characterise the next few years worth of Detective Comics.

As that back-up run began, there were still a number of Green Arrow stories appearing elsewhere, across World’s Finest Comics. Bob Haney brought the character back from the brink of writer Gerry Conway‘s sometimes outlandish indulgences (“The Relativity of Auntie Gravity”, World’s Finest Comics #261, February/March 1980), but gave his own globe-trotting spin by sending Ollie to the Caribbean (“Escape Me…Never!”, World’s Finest Comics #269, July 1981) or battling Count Vertigo in Vlatava or the Soviet Union (World’s Finest Comics #272 and #273, October/November 1981). Mike W. Barr would create more character-driven stories, such as newspaper columnist Queen refusing to divulge a source (World’s Finest Comics #279 – 281) and a fascinating story in which the mother of a crook Green Arrow accidentally killed in The Flash #217 (November 1972) returns to seek revenge!

There was also a notable appearance in Brave and the Bold #168 (“Shackles of the Mind”, November 1980) teaming the Emerald Archer up with Batman, along with a shot in DC Comics Presents #20 (April 1980). A digest-sized collector’s curiosity can be found in the DC Special Blue Ribbon Digest #23 (July 1982), which reprints a series of stories from Jack Kirby, Haney, O’Neil, Elliot Maggin, Neal Adams & Dick Giordano, but also a new framing storing by Barr and Dan Spiegle.

Detective Comics (1982 – 1986)

With the exception of two very notable issues, discussed below in further detail, Green Arrow’s final back-up series would be almost entirely scripted by Joey Cavalieri. This often forgotten series, and certainly not reprinted, saw the lefty hero standing alone against a tide of crime on the gritty streets of Ronald Reagan’s America. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1984 that Black Canary would regularly rejoin him as a partner in crime.

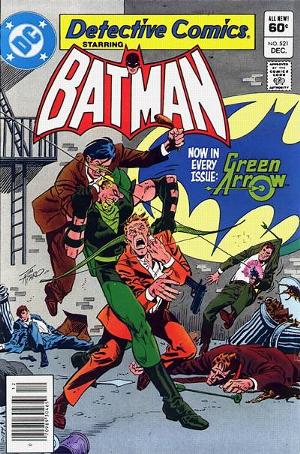

Across the 40-odd appearances that Green Arrow would make in the pages of Detective Comics between #521 (December 1982) and #567 (October 1986), the stories grew bigger in scope, often spilling out over three or four parts at a time. The 3-part “Mob Rule” (#523 – #525) deals with strikes and teamsters, while the “Getting Up” trilogy (#527 – #529) is about an urban artist named Ozone. It’s curiously Afghani terrorists in “Survival of the Fittest” (#530 – #532), while the 4-part “The Black Box” (#533 – #536) saga dealt with motorcycle gangs. It may not have been as “relevant” as the comics of the 1970s, but they were far from apolitical at a time when street violence, protests and economic downturn filled the newspapers.

Perhaps the most reprinted Green Arrow comics from this era are Detective Comics #549 and #550 (April/May 1985), thanks to being penned by Alan Moore with the equally legendary Klaus Janson on art duties. “The Night Olympics” is a 14-page story split over two issues, combining Moore’s earlier attempts at creating something grander out of a second-string character. In the introduction to the reprints of these issues as part of DC Universe: The Stories of Alan Moore (DC Comics, 2006, p.51), how Moore came to be involved in these two issues is explained:

“Almost immediately following Swamp Thing, Alan Moore was in demand. High demand, actually. As editors clamoured for his time, Alan was being given many tempting offers, including just about every character DC was currently publishing. Len Wein, the editor who initially brought Alan to work at DC, found out he was in a bit of a jam on his Green Arrow feature. The seven-page backup in Detective Comics was an opportunity to keep the character in the public eye until his popularity merited a mini-series or more.”

It begins in typical Moore humour, a mock-sporting commentary on a crook Arrow is chasing: “The first event was the four-hundred meter dash with television set and first-stage drug withdrawal”. It is probably ‘over-written’ by today’s standards, and seeks street-level poetry where a fairly standard and anti-climactic showdown can be found instead. Coupled with Janson’s grittier imagery, who was clearing the decks to work on The Dark Knight Returns with regular collaborator Frank Miller, it’s a strange mid-1980s experiment that foreshadowed what was to come in any number of careers and characters. Yet it is unmistakably the voice of Alan Moore, who excelled at making something operatic out of the everyday.

While the Detective Comics run is still only available in the original single issues, they are worth seeking out for an important transition period in Green Arrow’s history, and the marquee value of the creators involved in this period.

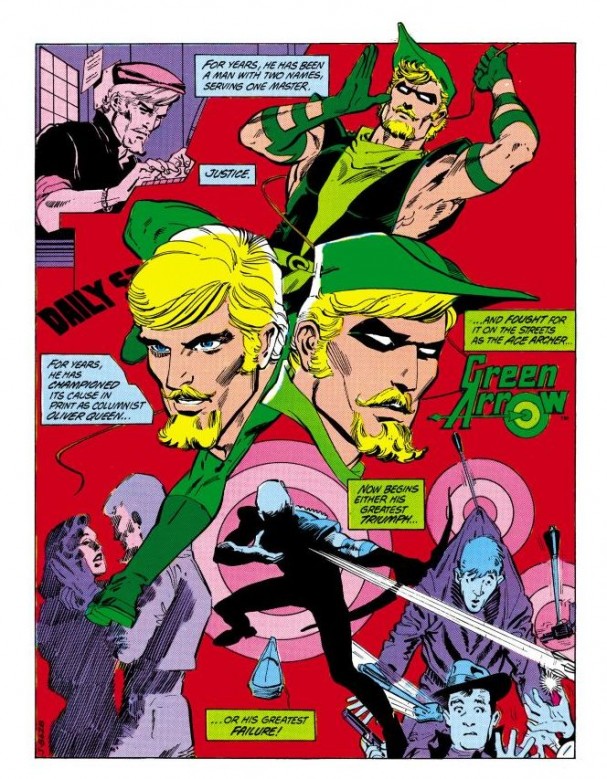

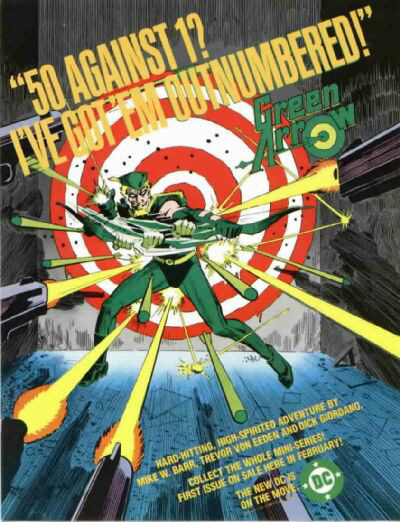

A Limited Solo Career: The 1983 Mini-Series

In the midst of the Detective Comics run, the most tentative attempt at a Green Arrow solo series was made in 1983. Written by Mike W. Barr and illustrated by Black Lightning co-creator Trevor Von Eeden, it had the difficult task of taking a character with over forty years of comic book history and presenting him in a way that was compelling enough to readers make him stand on his own for the first time. While it may not have achieved this goal initially, the series has stood the test of time as one of the first attempts to craft an extended story completely around Green Arrow.

Although it is now three decades old, Barr and Von Eeden’s Green Arrow is still socially and politically relevant today, perhaps even more so than it was at the time. Green Arrow is introduced in a manner not too dissimilar to the Daredevil and Batman comics at the time, attempting to take on crime in a sticky city, one perpetrator at a time. Living in an inner-city apartment, he is the urban everyman, trying to make ends meet and be something bigger than himself. His world is turned about when he is invited to the reading of a will from recently deceased friend Abby Horton, and suddenly becomes the beneficiary of a substantial sum of money. In a mostly investigative story, Ollie is not content to rest on his laurels, but rather uncover the truth about his friend’s death and how the oil industry was involved.

Setting up Green Arrow as odds with big business doesn’t seem too radical now, but in 1983 it was positively counter-culture to stand against Big Oil in a mainstream comic. While Barr doesn’t always gel with the character (at one point, the supposedly liberal Ollie even remarks “Blasted liberated women — we never shoulda let ’em out of the kitchen…”), his approach is to draw Oliver Queen/Green Arrow as something distinct from the rest of the DCU. Oliver regularly compares himself to Bruce Wayne and Batman throughout the issue, wondering how he is able to maintain the work-life balance that Oliver struggles with. It may not help the case for those that were still under the impression that Green Arrow was a bargain basement Batman, and perhaps a more apt comparison would be the run of Matt Fraction’s Hawkeye written some 30 years later. While Green Arrow regularly suits up, he is just an average guy who can’t seem to take a break, even when he is given one.

Setting up Green Arrow as odds with big business doesn’t seem too radical now, but in 1983 it was positively counter-culture to stand against Big Oil in a mainstream comic. While Barr doesn’t always gel with the character (at one point, the supposedly liberal Ollie even remarks “Blasted liberated women — we never shoulda let ’em out of the kitchen…”), his approach is to draw Oliver Queen/Green Arrow as something distinct from the rest of the DCU. Oliver regularly compares himself to Bruce Wayne and Batman throughout the issue, wondering how he is able to maintain the work-life balance that Oliver struggles with. It may not help the case for those that were still under the impression that Green Arrow was a bargain basement Batman, and perhaps a more apt comparison would be the run of Matt Fraction’s Hawkeye written some 30 years later. While Green Arrow regularly suits up, he is just an average guy who can’t seem to take a break, even when he is given one.

The introduction of the character of Abby Horton, the much older woman who becomes a friend to Oliver Queen prior to his being stranded on that fateful island, allows Barr to reframe the entire Green Arrow history within a more human context. Through her, we glimpse what Oliver Queen’s life might have been like before he learned the way of the bow, with her influence and companionship bringing out the inherent good in the playboy. A quick recap of his origin and career uses the Jack Kirby origin story, with Von Eeden even recreating the ‘leaf costume’ that graced Adventure Comics #256. Through Abby, the main thrust of the series is achieved, granting Oliver Queen and Green Arrow the simple and often moving gestures that continue to distinguish him from the rest of the DC family.

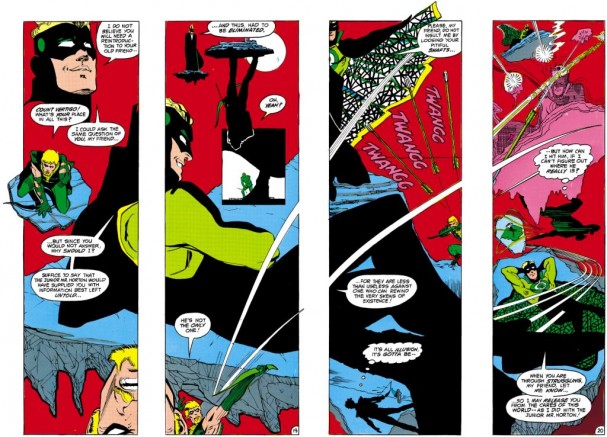

Von Eeden’s bold and experimental style remains light years ahead of its time, unable to be contained by page margins or panel borders. Von Eeden was no stranger to Green Arrow, doing many of the back-up stories throughout the 1970s for World’s Finest Comics. Von Eeden has stated that he “absolutely hated” what Vincent Colletta’s inks did to his artwork on that title, but his collaboration with the light touch of Dick Giordano on the miniseries produced some amazing results. Von Eeden’s attention to detail on character expression was a perfect companion to the increasingly complex version of Oliver Queen, and his stylish action often eschews splash pages for tightly controlled action. Yet there are also those panels where his sense of layout is revolutionary, especially when portraying the perspective-skewing Count Vertigo. Indeed, it’s only in 2013 that Andrea Sorrentino’s dizzying panels come close to matching this unique viewpoint on the character. Tom Ziuko’s colours are the final bold stamp on the series, brightly saturated to highlight the swashbuckling adventure aspects of the character, but also knowing when the complete absence of colour (such as pure white trees in the foreground of page 15 in issue #2) can be just as powerful.

Green Arrow (1983) didn’t set the sales charts on fire, and the character returned to the back-up pages of Detective Comics for the next few years, at least until Mike Grell got his hands back on the character and crafted his own mini-series. However, Barr and Von Eeden at least proved that it was possible to breathe new life into the character after forty years and treat him with some dramatic respect, even if the final issue threw in the ridiculous pirate, Cap’n Lash. Every decade seemed to craft the battling bowman for its own purposes, and in the few years before comics began to get especially self-referential and dark, this can be seen as a last hurrah for the Silver Age Green Arrow, filtered through his everyman Bronze Age persona. A bold experiment in art and storytelling, it may not have clicked with readers in 1983, but it can now be seen as one of the true forgotten gems of Green Arrow’s illustrious history.

A Pre-Crisis Wilderness and the first death of Green Arrow (1984 – 1986)

In the few remaining years before DC Comics boldly rebooted their line with the 1985/1986 Crisis on Infinite Earths event, readers could really only follow Green Arrow’s adventures in the pages of Detective Comics. 1983 would keep the past alive with a 7-issue reprint of the classic Green Lantern/Green Arrow run, while Green Lantern #165 (“The Curse of Krystayl”, June 1983) would also see the first team-up of Ollie and Green Lantern Jon Stewart . The following year, Green Lantern #180 (“Aftermath”, September 1984) saw the old Green Lantern/Green Arrow team briefly back together, and Crisis tie-in Green Lantern #195 (November 1985) would also feature a cameo from Green Arrow. Justice League of America #224 though #226 (March – May 1984) had Green Arrow and Black Canary once again fighting alongside the League, the first issue of which featured a visual tribute to The Amazing Spider-man #50’s “Spider-Man no more” on the cover.

Frank Miller and Klaus Janson’s The Dark Knight Returns was a significant appearance for Green Arrow in 1986, although the “Elseworlds” tale sits outside continuity. Although he appears on only a few pages of the 4-issue masterpiece, Miller’s Oliver Queen is instrumental to the narrative. Older, and missing an arm from an implied run-in with Superman, he is still formidable with a bow, and has evidently been working against “the system” in his own way over the years, not least of which is the sinking of a nuclear submarine. Cast as the antithesis of the military industrial complex, it’s the logical conclusion to Arrow’s brand of politics from the 1970s, and he is the one that predicts the showdown between Batman and Superman. Gripping the bow with one arm and his teeth, he delivers a Kryptonite arrow to Superman during said fight, and is ultimately a part of Bruce Wayne’s underground movement.

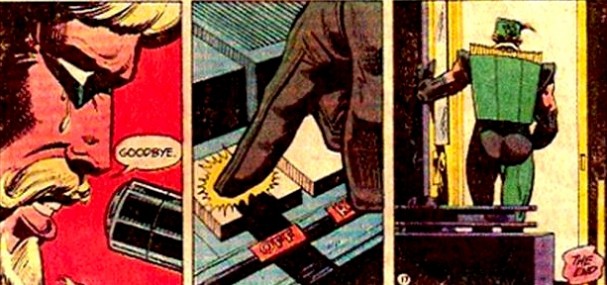

While Frank Miller was changing the face of Batman (and arguably comics) for the next several decades, Crisis on Infinite Earths was reshaping the DC Universe into a form that would largely remain in tact until the 21st century. The cross-title event brought to an end the notion of a “multiverse” in the DCU, one in which Earth-2 was largely populated with the heroes of the Golden Age. Designed to bring a streamlined continuity for new readers, it also meant the deaths of many classic characters, and the rebirth of others in the coming years. Green Arrow’s role was negligible in Crisis on Infinite Earths, although his “death” is witnessed on panel during issue #12 of the maxi-series. Decked out in the old-school green outfit with red gloves, the accepted wisdom is that this was an Earth-2 version that was being jettisoned.

While Frank Miller was changing the face of Batman (and arguably comics) for the next several decades, Crisis on Infinite Earths was reshaping the DC Universe into a form that would largely remain in tact until the 21st century. The cross-title event brought to an end the notion of a “multiverse” in the DCU, one in which Earth-2 was largely populated with the heroes of the Golden Age. Designed to bring a streamlined continuity for new readers, it also meant the deaths of many classic characters, and the rebirth of others in the coming years. Green Arrow’s role was negligible in Crisis on Infinite Earths, although his “death” is witnessed on panel during issue #12 of the maxi-series. Decked out in the old-school green outfit with red gloves, the accepted wisdom is that this was an Earth-2 version that was being jettisoned.

The symbolic “death of Green Arrow”, alongside the deaths of many other characters from various incarnations of the DC Universe, paved the way for fresh takes for a new and darker era for DC and comics more broadly. Indeed, the mid-1980s is generally thought of as the birth of the Modern Age of Comic Books, sometimes called the Dark Age of Comic Books, thanks to titles such as The Dark Knight Returns, Alan Moore’s Watchmen and Batman: The Killing Joke. By 1987, Green Arrow would be ready for another shot at a solo series, although it would be unlike anything that had ever been done for the character before. Mike Grell’s The Longbow Hunters would re-imagine Green Arrow as an “urban hunter”, a darker vigilante that had to once again deal with real world problems. It in turn would lead to the first ongoing series for the character, and a full decade of headline stories for the Emerald Archer. These will, of course, be the focus of the fourth chapter of this History of Green Arrow series.

Beyond the Comics

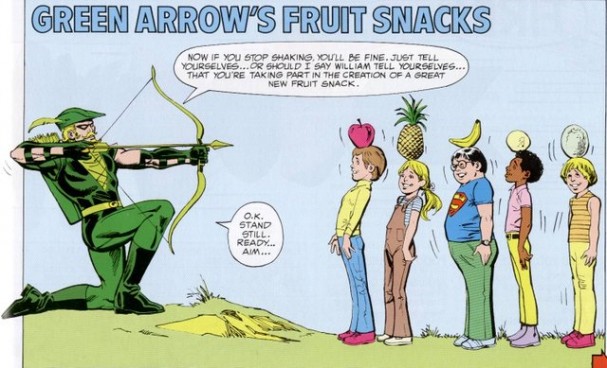

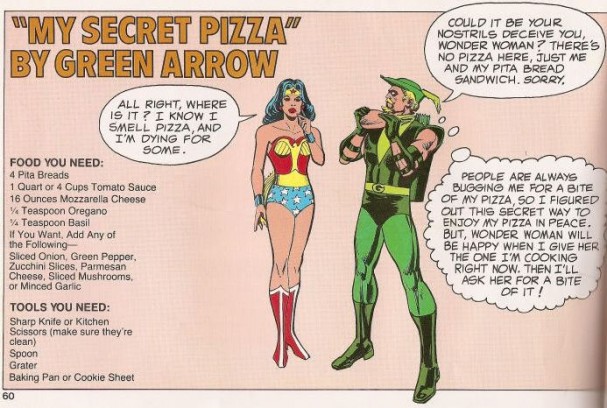

Green Arrow’s profile in the comics wasn’t exactly high during this period, so it’s understandable that there wasn’t a great deal of ephemera around either. However, there were a few surprising trinkets that are still floating around the eBay marketplaces. For instance, there’s the hardcover DC Super Heroes Super Health Cookbook (1981), featuring Green Arrow riding a fruit skewer through space on the cover. One of the recipes inside is for “My Secret Pizza” by Green Arrow (page 60), indicating that he may have actually invented the calzone years before its time! There’s also fairly early evidence as to why Oliver Queen would make a terrible father (see the picture to the right), as he lines up a group of kids to create a fruit snack – William Tell style! Perhaps he couldn’t be trusted with his own title until he was ready to stop torturing children in the name of healthy eating.

Green Arrow’s profile in the comics wasn’t exactly high during this period, so it’s understandable that there wasn’t a great deal of ephemera around either. However, there were a few surprising trinkets that are still floating around the eBay marketplaces. For instance, there’s the hardcover DC Super Heroes Super Health Cookbook (1981), featuring Green Arrow riding a fruit skewer through space on the cover. One of the recipes inside is for “My Secret Pizza” by Green Arrow (page 60), indicating that he may have actually invented the calzone years before its time! There’s also fairly early evidence as to why Oliver Queen would make a terrible father (see the picture to the right), as he lines up a group of kids to create a fruit snack – William Tell style! Perhaps he couldn’t be trusted with his own title until he was ready to stop torturing children in the name of healthy eating.

There were mugs and coins, including a set of bronze and gold plated coins from the “Cartoon Celebrities” line that are getting harder to find on the open market. Yet the most collectible and popular item of the era is the action figure released as part of the Super Powers Collection (pictured in the montage below). Released in 1985 for the 2nd series line-up, the surprisingly detailed figure featured an “archery pull” action by squeezing Green Arrow’s legs together. Fun fact: the 1991 Robin Hood line from Kenner reused Green Arrow’s body from this line, and his Merry Men were cobbling together from Hawkman, Batman, Captain Marvel, Lex Luthor, Robin, and Desaad! The figure even made the television commercial that screened during the 1980s, making this his second television appearance since his single Super Friends appearance in 1973.

In Part 4, we’ll explore the The Longbow Hunters in detail and journey through the gritty first 80 issues of Mike Grell’s historic six-year run.

>>Proceed to Part 4>>

Agree or disagree? Got a comment? Start a conversation below, or take it with you on Behind the Panel’s Facebook and Twitter!

If you are an iTunes user, subscribe to our weekly podcast free here and please leave us feedback.

7 pings

Skip to comment form

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) – His world is turned about when he is invited to the reading of a will from recently deceased friend Abby Horton … the eBay marketplaces. For instance, there’s the hardcover DC Super Heroes Super Health Cookbook (1981), featuring Green Arrow riding … […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986) – Across the 40-odd appearances that Green Arrow would make in the pages of Detective Comics between #521 (December 1982) and #567 (October 1986), the stories grew bigger in scope, often spilling out over three or four parts at a time. The 3-part “Mob … […]