You can almost set your clock to DC Comics reworking their universe. Since the mid-1980s and Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC has reset or tweaked the clock a number of times, filling in gaps or smoothing out inconsistencies in their narratives. So what is a crisis, and why are they so important?

You can almost set your clock to DC Comics reworking their universe. Since the mid-1980s and Crisis on Infinite Earths, DC has reset or tweaked the clock a number of times, filling in gaps or smoothing out inconsistencies in their narratives. So what is a crisis, and why are they so important?

Today, a “Crisis” in comic book terms indicates a monumental shift in the way we look at things, restructuring history and aligning the pieces so that they fit a new normal. It’s all fiction though, isn’t it? Does it need to make sense when it’s all made up? The answers to this become important when you think about our own place as readers in helping create these universe and making them real.

In 2015, the Marvel Cinematic Universe gets ready to add its twelfth film to the slate, with another nine already on the horizon. DC’s shared film universe prepares to release ten films set in the same world in the next five years. In the comics themselves Marvel and DC’s Secret Wars: Battleworld and Convergence events promise to change the way their entire universes fundamentally work. The reason this is all possible is that they exist in a shared universe, although this was not always the case.

So to understand DC’s “Crisis” is to understand the history and medium of comics. In this 5-part series, we’ll go through all of DC’s major crises, explain the major changes they caused and hopefully clear up some of the complex history that the Multiverse has woven over the years.

- Crisis Explained Part 2: Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985 – 1986) – COMING SOON

- Crisis Explained Part 3: Birth of the Modern Age and the Zero Hour (1987 – 1994) – COMING SOON

- Crisis Explained Part 4: Countdown to Infinite Crisis, Infinite Crisis and Final Crisis (1996 – 2010) – COMING SOON

- Crisis Explained Part 5: Flashpoint, The New 52, Multiversity and Convergenece (2011 – 2015) – COMING SOON

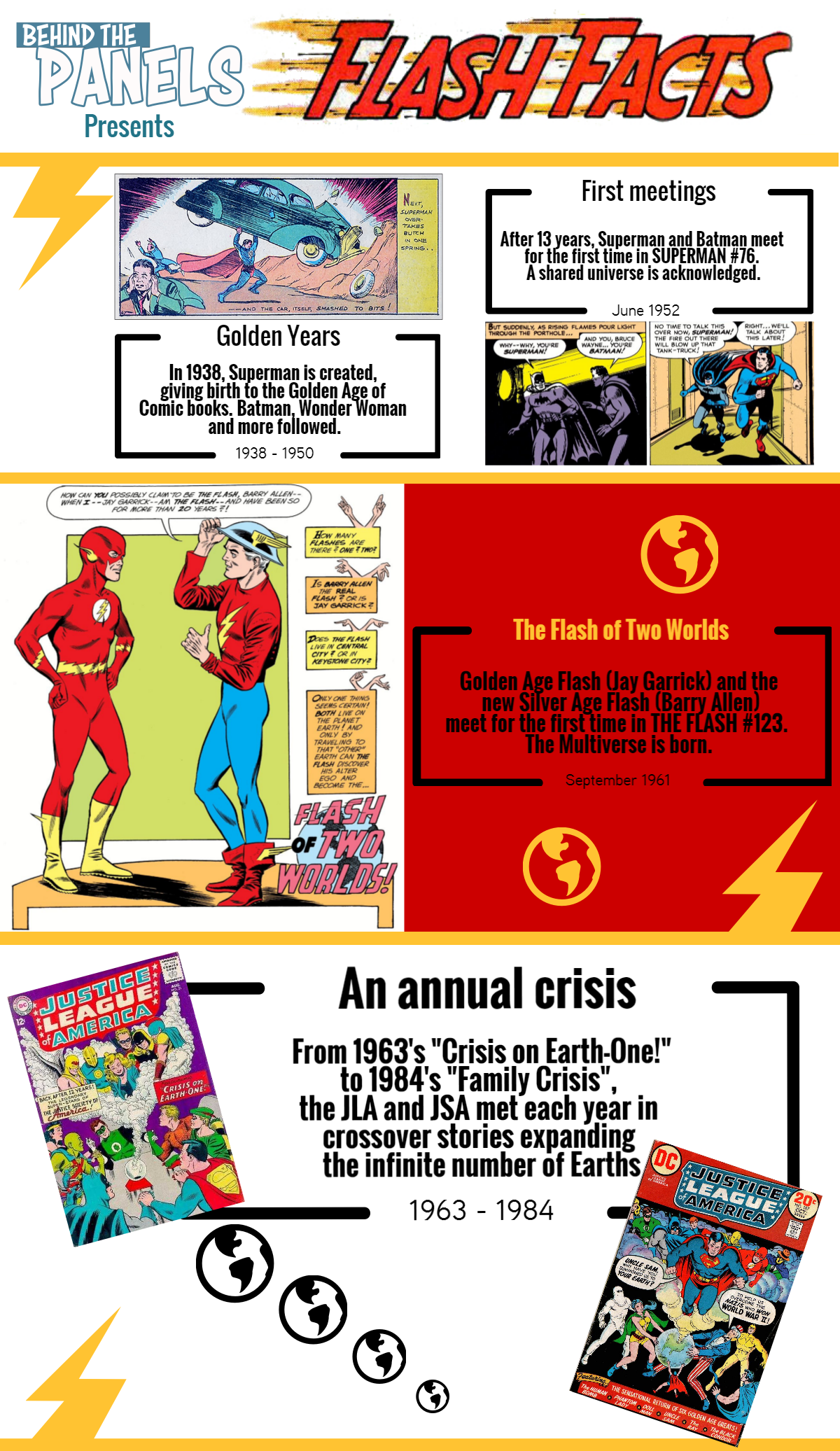

Don’t worry if there’s too much reading! There’s a Flash Facts section at the bottom on the page that tells the whole story in infographic form!

The Golden Age

The so-called Golden Age of comics lasted about 20 years, from the late 1930s to the tail end of the 1950s. This is not to suggest that comics got progressively worse, even if the dimishing monikers of ‘Silver’ and ‘Bronze’ Ages would suggest as much; or that they were at their peak during this time. In fact, commercial interest was the name of the game, and it was all about creating the next big newsstand sensation, chasing popular genres of jungle, western and romance stories. Disney licenced comics were also massive sellers, with Carl Banks a recognisable artist at the time.

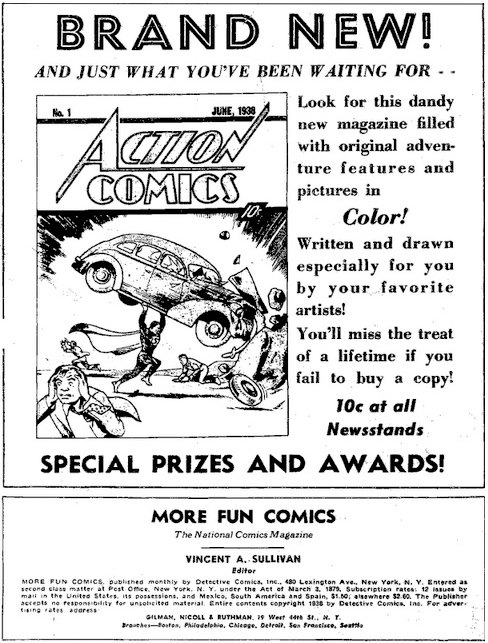

Yet it was during this era that many of the superhero archetypes were formed, many of which still last today. It’s also when many of the headliners were created: the trinity of Superman (1938), Batman (1939), and Wonder Woman (1941) came in rapid succession. Quality Comics’ Plastic Man (1941) and Will Eisner’s The Spirit (1940) graced the funny pages, while the wartime heroes like Captain America (1941) also emerged. Captain Marvel (1941), who was later known as Shazam, became one of the most popular characters of the era selling in excess of 1.4 million copies. Compare that with today’s figures, where a top 10 book sits around the 100,000 mark most months.

Yet despite being a “golden age” for sales and new characters, there still wasn’t a “DC Universe” to speak of. The characters often appeared in their own stories, and while they may have shared the odd cover here and there, it was more about sales than collaboration. That would change in the 1950s, and like all things, we can thank science for paving the way.

World’s Finest: first dates and shared worlds

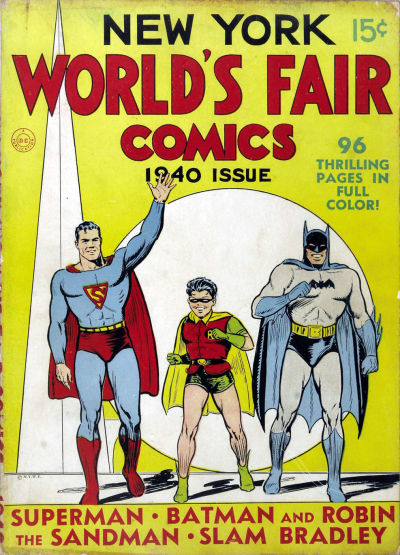

New York World’s Fair Comics (1940 Issue) – First published picture of Batman, Robin and Superman together

As hard as it is to believe, for the first 13 years of their shared publication history, Superman and Batman never teamed up on panel. The first merger of the Man of Steel and the Caped Crusader was a business one, as Action Comics publisher came together with Detective Comics Inc. to form what would eventually be known as DC Comics. The New York World’s Fair Comics 1940 Issue was the first published picture of Batman, Robin and Superman together. The publishing format of twin headliners in separate stories in the same publication would quickly be spun into World’s Best Comics (almost immediately renamed World’s Finest Comics), although the pair would not team-up within that publication until much later with World’s Finest #71 (July 1954). Yet this cover tacitly acknowledged a shared universe where Gotham City and Metropolis might have inhabited the same Earth.

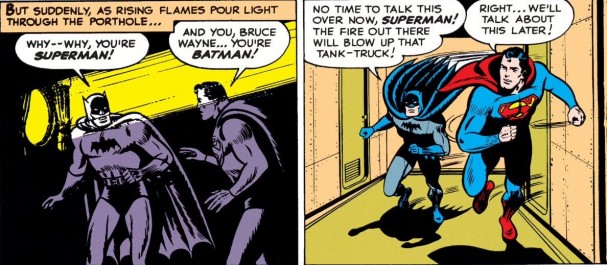

A more explicit acknowledgement would not come until 1952 with the publication of SUPERMAN #76 and Edmond Hamilton’s story “The Mightiest Team In the World,” with art by the one and only Curt Swan (along with Stan Kaye and John Fischetti). The story itself is the kind of fluff that was typical of the era: Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent board a cruise ship, but a booking mishap causes them to share a room. (It’s the kind of scenario that would send Frederic Wertham into pink fits two years later in his infamous Seduction of the Innocent (1954) tome, one that argued Batman and Robin’s relationship was a homosexual one). When an explosion on the docks forces the heroes to change in front of each other, their identities are revealed.

SUPERMAN #76 is a silly book. To buy into the premise, we have to suspend belief that neither billionaire Bruce Wayne or renown reporter Lois Lane seem to have any sway on this ship, resigning the two men to sharing a cabin. One sub-plot also involves the duo trying to convince Lois that Batman is trying to seduce her. The less-than-enlightened 1950s male version of Superman declares: “Say — I just thought of a way to keep Lois out of my hair! If you could pay attention to her — make her think you’re falling for her — and I pretend to be jealous, she’d be too occupied for amateur detective work!” It’s all a comedy of errors after that, Lois foiling them both by take the “cutest little chap” Robin out to dinner. Casual misogyny and 1950s mores aside for the moment, SUPERMAN #76 is significant for the first narrative acknowledgement that Superman and Batman (and by extension their “families” of Robin and Lois) inhabited the same world. It would ultimately pave the way for the formation of the first Justice League in BRAVE AND THE BOLD #28 “Justice League of America” (May 1960). Even if Batman and Superman’s first team-up was to foil Lois Lane, many have commented that this can be retroactively viewed as the first appearance of Earth-One, even if it wouldn’t be named as such for another decade. That, of course, would require the acknowledgement that there was more than one Earth.

Death and rebirth at the dawn of the Multiverse

“In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds…” – Comics Code Authority criteria, 1954

Then something unexpected happened. With the rise of horror and crime comics, led notably by EC Comics and their humour publication Mad (1952 – ) and the notorious Tales from the Crypt (1950 – 1955), it inevitably led to the attention of lobby groups and governmental committees wanting to stamp out this dangerous scourge. While Senator Joe McCarthy led his crusade against the “Red plots” of communism, Republican Senator Robert Hendrickson (and later Democratic Senator Kefauver) pushed the United States Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency through to action. Following the publication of Wertham’s aforementioned Seduction of the Innocent in 1954, and combined with the bad press that comics were receiving out of the Subcommittee hearing, the comics industry adopted the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a self-regulatory set of rules that specifically targeted depictions of sex and horror, effectively killing off the three major EC Comics horror titles in the process. Of particular note was the rule that ““In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.” That sounded like a job for a hero.

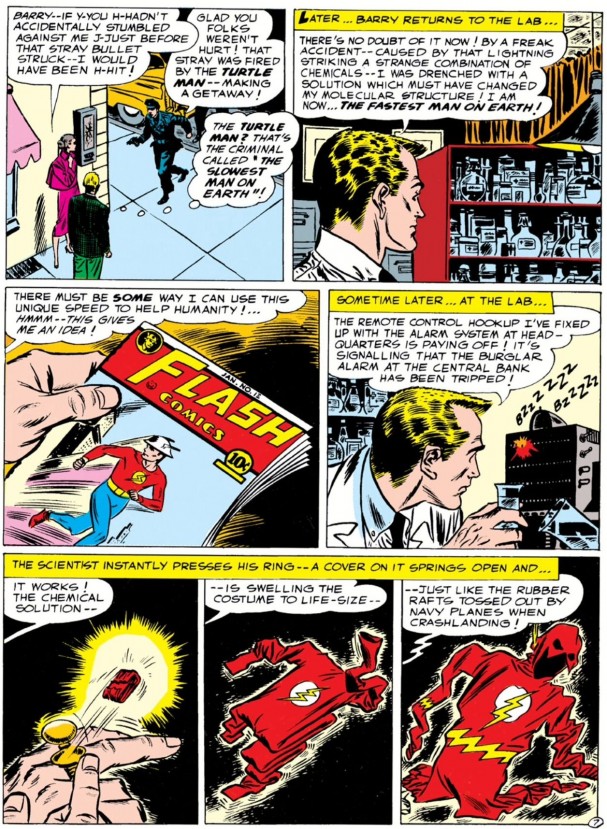

It’s for this reason that the Silver Age (roughly 1956 to the early 1970s) represent the ‘second great age of the superhero’. Heroes from the Golden Age were pushed to one side, with new versions of those characters born out of science and fighter pilots. Showcase #22 (1959) brought an all-new version of Green Lantern, an intergalactic cop, onto the scene in the form of Hal Jordan. Yet it was the earlier SHOWCASE #4 (October 1956), introducing a new character named Barry Allen as The Flash, that is largely cited as the birth of the Silver Age of comic books.

SHOWCASE #4 is important not just as the origin story of the modern version of The Flash and his successors, but for a hint of what would become one of the very foundations of DC’s version of a “Crisis.” Barry Allen is doused in chemicals and struck by lightning, an origin story that has been maintained through several crises, and even the television version of The Flash. The Robert Kanigher story may have also seen The Flash going up against Turtle Man, the world’s slowest man, but the combination of the electrifying Carmine Infantino and Joe Kubert artwork made this stand out on news stands. He was a streamlined version of the primary coloured heroes of the Golden Age with a mix of the scientific modernity and racing stripes of the 1950s. It also established that Jay Garrick, the original Golden Age Flash, was a fictional comic book character in Barry Allen’s world. The message was clear: this new Flash was more real than your daddy’s Flash, a miracle of modernity. It also meant that the heroes of the 1930s and 1940s were, by implication, in a different reality to this Flash and his contemporaries. Thus, the seeds were sewn for what would eventually become the Multiverse.

“A Flash of Two Worlds”: Enter the Multiverse

Following a few appearances in Showcase, The Flash/Barry Allen would pick up his ongoing adventures from Flash Comics #105 (March 1959), continuing Jay Garrick’s numbering exactly 10 years after that book had been cancelled. Yet things were about to get even more meta, when Jay Garrick and Barry Allen’s worlds collided in an almost unprecedented move by DC, not only bringing the aforementioned fictional story into Barry Allen’s reality, but involving the reader as well.

Following a few appearances in Showcase, The Flash/Barry Allen would pick up his ongoing adventures from Flash Comics #105 (March 1959), continuing Jay Garrick’s numbering exactly 10 years after that book had been cancelled. Yet things were about to get even more meta, when Jay Garrick and Barry Allen’s worlds collided in an almost unprecedented move by DC, not only bringing the aforementioned fictional story into Barry Allen’s reality, but involving the reader as well.

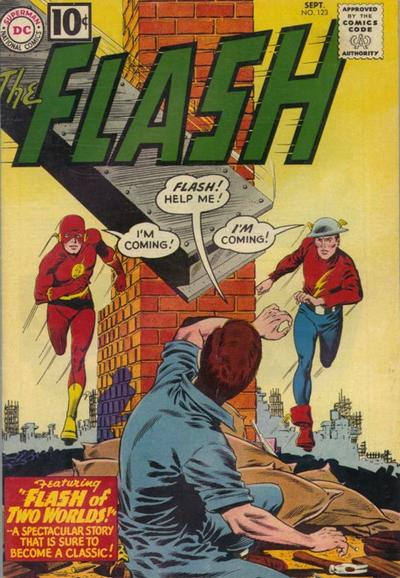

In what is now considered a prelude to the annual “Crisis” events that DC published, the “Flash of Two Worlds” story published in THE FLASH #123 (September 1961) may rightfully be considered as one of the most important in comic book history. Written by Gardner Fox, under the genius guidance of editor Julius Schwartz, with art from the incomparable Infantino (with Joe Giella), “Flash of Two Worlds” changed the way we look at comics.

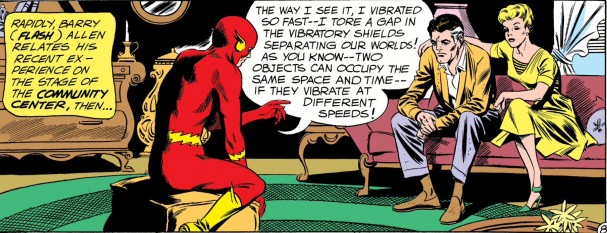

Barry Allen as The Flash is performing for charity, when the right vibration of molecules sends him to what turns out to be Keystone City, the home of the Golden Age Flash. The world, later established as Earth-Two, is the physical manifestation of the old DC super heroes, with that world’s Flash going into retirement at the same time DC Comics stopped publishing and writer Fox stopped creating new Jay Garrick stories. Following a team-up to stop some alternate Earth villains, Garrick decides to come out of retirement and resume his tenure as the Flash of Earth-Two.

Flash discovers the multiverse in The Flash #123 (1961) – “The Flash of Two Worlds”. Writer: Gardner Fox. Artist: Carmine Infantino with Joe Giella

The narrative of THE FLASH #123 is essentially a romp, a loving throwback to a literal Golden Age where the crooks and their motivations were far less complex. The effects of THE FLASH #123 can, like the multiverse it created, be witnessed in the real and fictional worlds. From a publishing standpoint, positive fan feedback gave DC the confidence to revive other Golden Age characters and the JSA in future issues of The Flash, with further team-ups occurring in The Flash #129 “Double Danger on Earth” (June 1962) and The Flash #137 “Vengeance of the Immortal Villain” (June 1963). It would ultimately lead to annual team-ups with the JSA (see below), and a whole new era for the Golden Age characters.

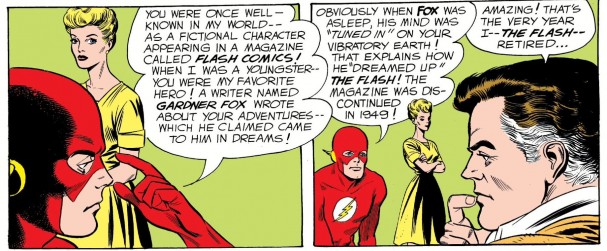

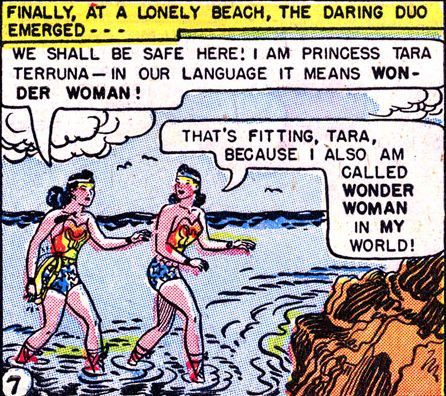

On a far more existential level, this meeting posited the very real notion of the multiverse, Having been seriously considered in scientific circles at least since Hugh Everett’s work in 1957, the “many worlds theory” or parallel dimensions were nothing new to science fiction literature or film. A few years earlier, Wonder Woman #59 “Wonder Woman’s Invisible Twin” (May 1953), one of DC’s first forays into the multiverse came with Robert Kanigher and Harry G. Peter’s story about Tara Terruna, an identical Wonder Woman from a parallel Earth (much later established to be Earth-59) complete with her own multiversal villain Duke Dazam. Under Schwartz and The Flash, it was being used a device that fundamentally shifted what the DC “universe” meant. It was no longer a single world filled with heroes, but part of wider network where every contradictory story was real to somebody. As writer Grant Morrison points out in his Supergods, it necessarily meant that the reader was part of this vast process as well:

“If Barry lived on a world where Jay was fictional, did that mean we, as readers, were also part of Schwartz’s elegant multiversal architecture? It did indeed, and it was soon revealed we all lived on Earth Prime.” – Grant Morrison, Supergods

Are we all part of someone else’s story? The Flash #123 (1961) – “The Flash of Two Worlds”. Writer: Gardner Fox. Artist: Carmine Infantino with Joe Giella

For if Gardner Fox was a writer in The Flash’s world, and he was also the creator of The Flash in our world, that also meant that we were aiding The Flash’s adventures and life force by the very act of reading a comic. Morrison cites the legendary cover to The Flash #163 “The Flash Stakes His Life–On–You!” (August 1966) from a few years later, where the character directly appeals to the audience on the cover with “STOP! Don’t pass up this issue! My life depends on it!” Fox and Schwartz took the idea even further a few years later when Earth Prime was properly revealed in The Flash #179 “The Flash–Fact or Fiction? (May 1968), where Barry found himself trapped on Earth Prime, where Earth-One, Earth-Two and subsequently created Earths only existed in fiction. Barry actually seeks out editor Julius Schwartz by looking up his name and office address in comic based on his own adventures. He ultimately returns home with the aid of Schwartz and a hastily constructed Cosmic Treadmill, an inter-dimensional device that would become incredibly important in later stories.

It’s a notion Morrison would continue using over the years, investing his work The Invisibles with a hypersigil, or writing himself into the final issue of his Animal Man run. Indeed, Chuck Jones had played with that idea on screen during the 1950s with the surreal Daffy Duck short Duck Amuck in 1953. (Morrison continues to address these notions in The Multiversity, which we will return to in a later chapter). Indeed, it’s probably worth noting that even the writing (and reading) of this article adds another layer to that multiversity.

So The Flash, and by extension his fellow Justice Leaguers, were not alone in the universe. Indeed, their universe was not the only one on the block, and the few Earths that we had been introduced to so far were only just the beginning. The restoration of the Golden Age heroes would lead to new creative opportunities, and dozens of team-ups over the next 20 years. Yet it would also incredibly complicate DC’s continuity, leading to the introduction of the word “Crisis” into this soon to be “infinite” number of Earths.

An annual “Crisis” (1963 – 1984)

With the stage set for alternate Earths, DC took the opportunity to have those worlds collide whenever possible. JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA #21 “Crisis on Earth-One!” (August 1963), written by Gardner Fox, penciled by Mike Sekowsky and inked by Bernard Sachs, became the first JLA/JSA crossover that led with the “Crisis” label. Fighting a common set of foes, who at one point hid “in a misty borderland between two Earths — separated by only a few degrees of vibratory speed…”, it’s another story that ends with dual set of hero victories. Hawkman gleefully chips in “We’re going to keep in touch! There’s no telling when we may be called upon to join forces again!” Over the next two decades, it certainly became easier to tell with a series of annual crossovers in the pages of Justice League of America, most of which had the word “crisis” somewhere in the title. As Mark Waid notes in the introduction to the first volume of a series of trade paperbacks now called Crisis on Multiple Earths:

“So successful was the stunt that, for the next quarter-century, the JLA/JSA team-ups were an annual affair in the summer issues of JUSTICE LEAGUE OF AMERICA. With each…”crisis”…the JSA enjoyed more and more of the limelight, gradually moving from the role of “guest stars” to “co-stars” and even edging the League completely out of their own comic for a month in 1968’s JLA #64…” – Mark Waid, Crisis on Multiple Earths

Throughout the decades we’d be introduced to a “flipped” Earth-Three (Justice League of America #29 and 30, 1964), where heroes and villains have changed place to form the Crime Syndicate of America, or an Earth-X (Justice League of America #107 and #108, 1973) on which the Nazis never lost the Second World War and it was still raging. When DC would acquire other companies, those too would be folded into the multiverse, as evidenced by Fawcett’s characters – including Shazam/Captain Marvel, The Shade and Bulletman/Bulletgirl – appearing on Earth-S (Justice League of America #135, 136, and 137, 1976). That last crossover was so big, that it went over three issues instead of the traditional two, showing just how huge the annual event had become. Indeed, reading the “Crisis” stories in isolation is a study in how comics writing and art-driven styles changed over the course of 20 years.

By the 1970s, almost everything published under the DC label or owned by it was considered to be part of the Multiverse, even if they hadn’t been designated official names yet. The storytelling possibilities were limitless – or “infinite” if you prefer. Yet most of the crossovers tended to be limited to these summer events. Nevertheless, continuity began to get more complicated over the years. Inconsistencies in origins were evident to a more sophisticated audience who were demanding a dark kind of comic book by the mid-1980s. Another “Crisis” was brewing, and this time the body count would be commensurate with the Dark Age of the eighties.

Flash Facts

Confused yet? Well instead of reading 3000 words, we’ve made you this chart as well. It makes us wonder why we did all that research…

In Part 2, we’ll look at the year-long maxi-series that changed the face of comics forever when we delve into CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS.

Want to keep up with the latest? Got a comment or correction? Start a conversation below, or take it with you on Behind the Panel’s Facebook and Twitter!

If you are an iTunes user, subscribe to our weekly podcast free here and please leave us feedback.

3 pings

[…] Flash (Barry Allen) for the first time in The Flash #123. Most agree that this was the moment the Multiverse was born, allowing DC to continue publishing older characters as the Justice Society of America on a […]

[…] Speaking of THE FLASH heading deeper into comic book territory, the teaser poster released for the second season not only gives us our first look at Teddy Sears as Jay Garrick, the original comic book Flash, but pay tribute to one of the most important comics of all time: The Flash #123. In essence, it’s the comic that established the DC Multiverse. […]

[…] 2. Gray, R. (2015, March 19). Crisis Explained Part 1: Enter the Multiverse (1940 – 1984). Retrieved November 26, 2015, from https://behindthepanels.net/crisis-explained-part-1-enter-the-multiverse-1940-1984/ […]