Green Arrow has made a big splash in the last few years, even getting his own television series with Arrow hitting the small screen in 2013. He’s graced animated series, major comic book crossovers and survived every incarnation of the DC Universe. Yet he wasn’t always a star player, often taking a supporting role to other characters, or simply being unfavourably compared with a certain Dark Knight.

Green Arrow has made a big splash in the last few years, even getting his own television series with Arrow hitting the small screen in 2013. He’s graced animated series, major comic book crossovers and survived every incarnation of the DC Universe. Yet he wasn’t always a star player, often taking a supporting role to other characters, or simply being unfavourably compared with a certain Dark Knight.

In the first of what is hope will be many retrospectives, Behind the Panels takes you through the publication history of the character, explore his fictional origins and the many writers he’s had over the years. From Mort Weisinger, through Jack Kirby, Denny O’Neill, Neal Adams, Mike Grell, Chuck Dixon, Kevin Smith, Brad Meltzer, Judd Winick, Jeff Lemire and even Alan Moore.

Perhaps one of DC’s longest running characters that has sat outside the mainstream until recently; we hope you enjoy this look back. We acknowledge the excellent work already done by Alan Kistler, Scott Tipton, Jeff Reid and Bob Hughes that we referenced in compiling this series of articles. It’s a labour of love, and it is good to know so many people share such affection for the character. This article actually began as a one-shot piece, but as we uncovered Green Arrow’s rich history, the scope expanded.

Additional Reading:

- The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 2 – Hard Travelling Through the Wilderness Years (1970 to 1979)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 4 – Longbow Hunting Through the Wonder Years (1987 – 1993)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 5 – At the Crossroads of Death with Connor Hawke (1994 – 2000)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 6 – Quiver through Brightest Day (2001 – 2011)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 7 – Losing the Beard: The New 52, ‘Arrow’ and the Contemporary Age (2011– )

In this first part, we cover his first appearances through to his first beard…

Golden Age (1941 – 1956)

Mort Weisinger had already been working as a writer and editor for a few years before and after his military service around the Second World War when he moved from Standard Magazines to National Periodicals, the company that would eventually become DC Comics. He would eventually serve as editor of DC’s Superman titles (following a stint on The Adventures of Superman TV series), a tenure that would drive Roy Thomas to Marvel and label him a “malevolent toad.”

Weisinger’s origin story was based in the kind of fandom modern geeks can relate to. The son of a Jewish businessman in the garment trade, he was keenly interested in science fiction from an early age. Indeed, in 1932 he co-created Time Traveller, one of the first science-fiction magazines with super fan Forrest James Ackerman and Julius Schwartz, one of the key figures of DC’s Silver Age. With Schwartz he would form the first literary agency to specialise in sci-fi, horror, and fantasy. Moving into editing, Weisinger was responsible for almost 40 titles in the Standard Magazine line by the time of the Second World War.

According to an interview in The Amazing World of DC Comics #7 (cover date July-August 1975), as a writer/ editor Weisinger had to “dream up some new characters”, and one of his first jobs following his army service was More Fun Comics #73 (1941). Hubert H. Crawford (in Crawford’s Encyclopedia of Comic Books, 1978), notes that a “score of superheroes” were introduced “in order to smother what might be interpreted as a publishing blunder”, namely the bungled origin and gradual watering down of the character of Dr. Fate. As such, this particular issue was significant for the first appearance of Aquaman, whom Weisinger also co-created, but also for introducing us to the dynamic duo of archers, Green Arrow and his sidekick Speedy in “The Case of the Namesake Murders”. As such 25 September 1941 became a “green-letter day” in the history of comics publishing.

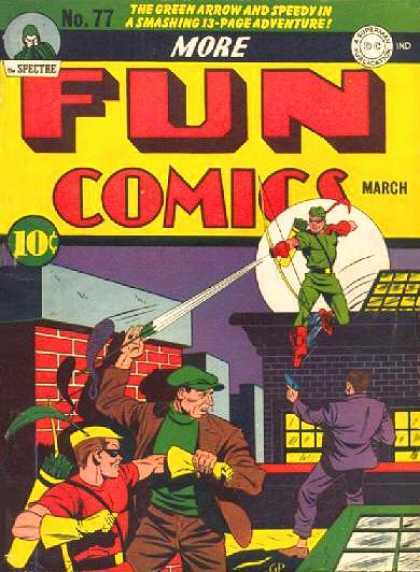

Green Arrow had clear influences from Robin Hood, but Weisinger also took a cue from the serialised film adaptation of Edgar Wallace’s The Green Archer. Co-created with artist George Papp, the character may have been a blatant analogue for the already popular Batman – complete with Arrow Cave, Arrow Car, Arrow-Signal and a clownish foe named Bulls-Eye – but he was soon popular enough to get his own cover with More Fun #77. Weisinger always denied the connection between the two characters, stating in Secret Origins of the DC Superheroes (1976):

“I wasn’t remotely influenced by Batman. My Green Arrow was a streamlined Robin Hood – a law-abiding Robin Hood. Then I added props – the Arrowmobile, for one, and I got into the business of creating new kinds of arrows.”

Weisinger’s two parallel creations of Vigilante and Green Arrow are said to bring “cowboys” and “Indians” to a modern metropolis. By More Fun Comics #89 (“The Birth of the Battling Bowmen”), illustrated by Cliff Young and Steve Brodie, the first origin story came into play, and it was one that significantly differs from the later island stories. Growing up alongside Native Americans, Oliver Queen learned to appreciate the lifestyle of the people and gained some proficiency with a bow. When museum curator and archaeologist Queen has his collection ransacked, the subsequent adventure teams him up with a kid that would eventually become Speedy. Speedy himself is a survivor of a plane crash, and partly raised by Native Americans. This origin was a clear attempt at solidify its ties to the popular Western genre, as well as the adventure stories that would eventually inspire the likes of Indiana Jones.

Many of the things that Golden Age Green Arrow is most closely associated with, and indeed is still tied to, were birthed over the course of many years especially in the pages of World’s Finest (mostly by George Papp) and Adventure Comics, where Green Arrow more appropriately transitioned after More Fun Comics. ‘Trick arrows’ are so much a part of the character’s mythology, it scarcely seems to matter that he didn’t use them for large chunks of his early career. According to Bob Hughes, the first outlandish trick arrow (a boomerang arrow) turned up in Adventure Comics #108 (“Contest for Champions”, 1946), but Aaron Bias has identified that the first was a bolo (or bolas) arrow as early as More Fun Comics #77 (“Doom over Gayland”, 1942). However, the infamous Boxing Glove Arrow turned up in Adventure Comics #118 (“The Weather Wizard”, 1947), against the only appearance of the Storm King. Weisinger once commented:

“I was afraid a reader would say one day ‘How the hell can he carry that many arrows in his little bag?’ He had everything from A to Z in there. In real life, he’d need fifty plastic garbage bags to haul them.”

Green Arrow would carry on in this fashion for the remainder of the Golden Age, as (notes Paul Levitz in 75 Years of DC Comics: The Art of Modern Mythmaking), “Boxing glove shafts gave way to tear gas arrows, bubblegum arrows, buzz saw arrows – whatever made for the easier solution problem at hand.” Clearly a narrative arrow was not available at this time.

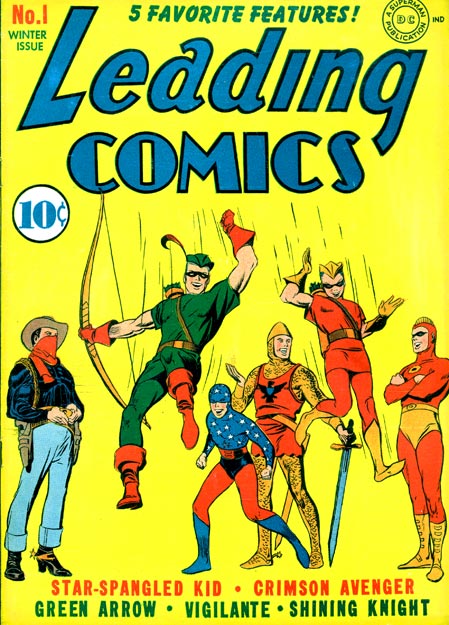

Green Arrow and Speedy appeared in the first 14 issues of Leading Comics (1942 – 1945) as charter members of the Seven Soldiers of Victory. DC at the time was publishing as National and All American Comics, and in joining the National team book, Green Arrow and Speedy were already stars. Joining him for a bit of wartime patriotism was the Star-Spangled Kid and Stripesy, the time-displaced Shining Knight, the Crimson Avenger and sidekick Wing, and of course, Weisinger’s other creation, the singing cowboy on a motorbike known as the Vigilante. Critic and cartoonist R.C. Harvey notes in his introduction to the Seven Soldiers of Victory Archives [DC Archive Editions], the Soldiers “were recruited from the ranks of characters who had just debuted.” Yet there’s some real historical value here, not least of which because of the involvement of artist George Papp on several issues, the legendary Jerry Siegel (co-creator of Superman), Mort Meskin and Bill Finger, the uncredited co-creator of Batman.

Green Arrow and Speedy appeared in the first 14 issues of Leading Comics (1942 – 1945) as charter members of the Seven Soldiers of Victory. DC at the time was publishing as National and All American Comics, and in joining the National team book, Green Arrow and Speedy were already stars. Joining him for a bit of wartime patriotism was the Star-Spangled Kid and Stripesy, the time-displaced Shining Knight, the Crimson Avenger and sidekick Wing, and of course, Weisinger’s other creation, the singing cowboy on a motorbike known as the Vigilante. Critic and cartoonist R.C. Harvey notes in his introduction to the Seven Soldiers of Victory Archives [DC Archive Editions], the Soldiers “were recruited from the ranks of characters who had just debuted.” Yet there’s some real historical value here, not least of which because of the involvement of artist George Papp on several issues, the legendary Jerry Siegel (co-creator of Superman), Mort Meskin and Bill Finger, the uncredited co-creator of Batman.

As a backup character without his own headline title for many decades, collecting Arrow in this era is particularly problematic, as the primary character appearances are often what drives the market value through the roof. Case in point is the very first appearance of Green Arrow, which is significant enough without also adding Aquaman’s introduction and an early Johnny Quick story into the mix. The number of surviving copies is also incredibly low, although a number of the key issues have had various reprints over the years. That said, more readers would become familiar with the Silver and Bronze age version of the character, who had some help growing thanks to a guy named Kirby.

Silver Age (1956 – 1969)

For the uninitiated, the Silver Age of Comic Books is roughly 1956 to just before 1970, a time when the post-Second World War horror stories were in decline thanks to the introduction of the restrictions imposed by the Comics Code Authority. As such, superhero stories once again began enjoying the limelight, and many of the characters that still hold sway today were launched in this period, especially for Marvel. However, over at DC Comics, the Silver Age is rightly said to begin with Showcase #4 (in October 1956) which introduced a new version of The Flash, under editor Julius Schwartz, writer Gardner Fox, and artist Carmine Infantino. It was during this period that Justice League of America launched (in which Green Arrow would soon appear), and Marvel ultimately followed with Fantastic Four. As unlikely as it seems, Green Arrow survived this transition.

For the uninitiated, the Silver Age of Comic Books is roughly 1956 to just before 1970, a time when the post-Second World War horror stories were in decline thanks to the introduction of the restrictions imposed by the Comics Code Authority. As such, superhero stories once again began enjoying the limelight, and many of the characters that still hold sway today were launched in this period, especially for Marvel. However, over at DC Comics, the Silver Age is rightly said to begin with Showcase #4 (in October 1956) which introduced a new version of The Flash, under editor Julius Schwartz, writer Gardner Fox, and artist Carmine Infantino. It was during this period that Justice League of America launched (in which Green Arrow would soon appear), and Marvel ultimately followed with Fantastic Four. As unlikely as it seems, Green Arrow survived this transition.

Thanks to the aforementioned World’s Finest and Adventure Comics appearances, Green Arrow had settled into a fairly lengthy run of stories from 1946 through to this period. Most of these issues are fairly forgettable, including quirky entries like Adventure Comics #178’s “The Ape with the Human Brain” (1952), or 1952’s “1001 Ways to Kill Green Arrow” (Adventure Comics #174), in which a mastermind writes a book of the same title and sells it to a group of crooks who understandably make use of it. A sure sign of the decline must be 1963’s World’s Finest #131, where Oliver Queen twists his ankle playing tennis, and sends a decoy Green Arrow out with Speedy so the bad guys don’t catch on (“The Green Arrow Dummy”). Although a number of them are yet to be reprinted in any form, Green Arrow continuity has not suffered terribly from their absence.

While the Flash, Green Lantern, Atom and Hawkman all got the reboot treatment, Green Arrow and Speedy retained their original identities for better or for worse for the time being. However, in 1958, Green Arrow was given a shot to the centre of his target with artist Jack Kirby coming on board for Adventure Comics #250, even if Bill Finger’s story (“Green Arrows of the World”) is a bit of non-canonical silliness. A few issues later, Jack Kirby would write (with Ed Herron) and pencil what is arguably the single most important Green Arrow story in the character’s seven decades. This re-telling for the Silver Age saw wealthy playboy Oliver Queen stranded on an island, crafting his first green camouflage suit and net arrows. Fighting off pirates to board a ship to get him off the island, it is the framework that would later serve Mike Grell’s retelling (The Longbow Hunters, 1987), Andy Diggle and Jock’s revisionist version (Green Arrow: Year One) and much of the flashback material in the Arrow TV series.

What is most interesting is how little Kirby cared for the character, never reaching any agreement with the editors over his 11 stories with the Emerald Archer. In an introduction to The Jack Kirby Omnibus Volume 1: Starring Green Arrow (DC Comics, 2011), Mark Evanier talks about this attitude:

“Kirby didn’t particularly like the character, and, oddly enough, neither did Jack Schiff, Green Arrow’s longtime editor. When Kirby suggested revamping the feature so that it might blossom into more than just a back-up strip, Schiff was interested. Kirby’s proposal gave it a new and unique science-fiction slant, Schiff liked it and Kirby immediately wrote at least one story that reflected his new ideas. Then the arguments started. Others in the office, mainly Weisinger…objected to the makeover. Schiff suggested toning down the new elements, and eventually they were toned down to the point that Kirby felt they were too compromised to make a bit of difference.”

Kirby didn’t get his way, and he mostly ended up working on scripts sold before his time or were significantly re-written once he was aboard to make them more ‘traditional’ Green Arrow stories. Elements of Kirby’s sci-fi leanings can be seen in a rare two-part story over Adventure Comics #252 and #253, “The Mystery of the Giant Arrows” and “Prisoners of Dimension Zero”. Here we meet Xeen Arrow, an equivalent hero from another planet who must get help from Green Arrow and Speedy before an inter-dimensional rift closes. While it may have been a compromised story, one can see indications of a new demand from writers and readers alike for a different kind of story. The 1950s saw a massive upswing in alien and other extra-terrestrial based stories, and the comic book industry was no exception. In fact, Green Arrow and Speedy were eventually knocked out of the pages of Adventure Comics by the arrival of future kids, the Legion of Super-Heroes.

Elsewhere in the pages of Green Arrow, there was still a degree of the character finding himself through random encounters with an assortment of strange characters, including the introduction of the Clock King, Slingshot, the Camoflague King and the inevitable introduction of a Miss Arrowette in the pages World’s Finest Comics #113 (November 1960), written by Dave Wood with Lee Elias on art duties. Another sign that the book was getting behind the times, Arrowette (aka Miss Bonnie King) featured an arsenal of trick arrows that included the Powder Puff Arrow, a Nail File Arrow, the Hair Pin Arrow and other feminine twists. A far cry from the battler for social justice that Green Arrow would one day represent, Arrowette proves she can’t be a hero because of clumsiness and her vanity getting in the way of wearing a mask!

Elsewhere in the pages of Green Arrow, there was still a degree of the character finding himself through random encounters with an assortment of strange characters, including the introduction of the Clock King, Slingshot, the Camoflague King and the inevitable introduction of a Miss Arrowette in the pages World’s Finest Comics #113 (November 1960), written by Dave Wood with Lee Elias on art duties. Another sign that the book was getting behind the times, Arrowette (aka Miss Bonnie King) featured an arsenal of trick arrows that included the Powder Puff Arrow, a Nail File Arrow, the Hair Pin Arrow and other feminine twists. A far cry from the battler for social justice that Green Arrow would one day represent, Arrowette proves she can’t be a hero because of clumsiness and her vanity getting in the way of wearing a mask!

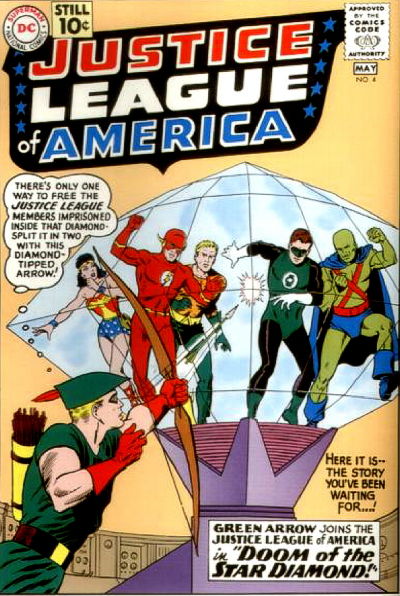

Yet perhaps one of the most important unions Green Arrow formed was in the pages of Justice League of America, with Green Arrow one of the first non-foundation members to be let into the club. In the historic Silver Age union by writer Gardner Fox, “The Doom of the Star Diamond” sees Ollie formally inducted in the League after breaking them out of a giant diamond-shaped structure with his own diamond-tipped arrow. He would join them on some of the first multiverse crises (“Crisis on Earth-One!” and “Crisis on Earth-Two!” in Justice League of America #21 and #22 respectively), and generally be a good sport of a supporting player. His shift in attitude would come with a change of writer.

A new attitude, a new look

Dennis “Denny” O’Neil began his run with Justice League of America #66, following a 65 issue stand from Gardener Fox, and immediately showed an affinity with a character he would later define in his acclaimed Green Lantern/Green Arrow run of the 1970s. In an issue that would later drip with significance, “Divided — They Fall!” (November, 1968) shows the League turning down a job they deemed to be too trivial. Green Arrow is furious that they won’t help out all those in need, and storms off. Superman spookily feels that Arrow is acting like a brat, while Wonder Woman sympathises that he must feel inferior. Levitz notes the significance of this issue in 75 Years of DC Comics:

“It was a jarring transition: Fox’s stories were rich in plot but light on characterization. By contrast, O’Neil concentrated less on complex stories and more on giving each hero an individual voice for the first time. Fox’s Leaguers were interchangeable; O’Neil’s bantered, bickered, fought and joked. Under Fox, they were a team because of their similarities; under O’Neil, they were a team despite their differences.”

This perhaps foreshadows the “gods versus humans” arguments that would later become a focus of darker edged comics in the 1980s and beyond. Significantly for Green Arrow, this was the first indication of his attitude towards social justice that would ultimately see him take Green Lantern on the road to teach him about the ‘real world’. In this issue, however, he merely apologises for “flying off the handle”.

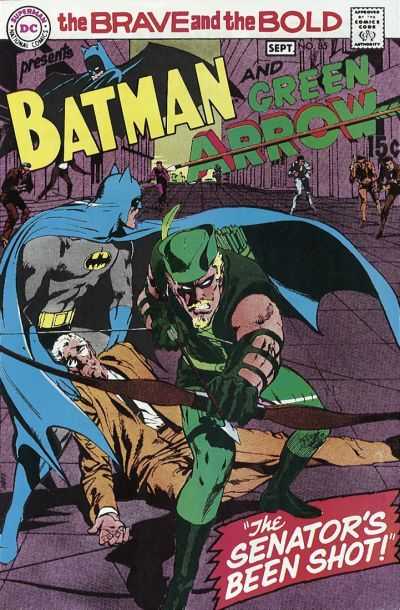

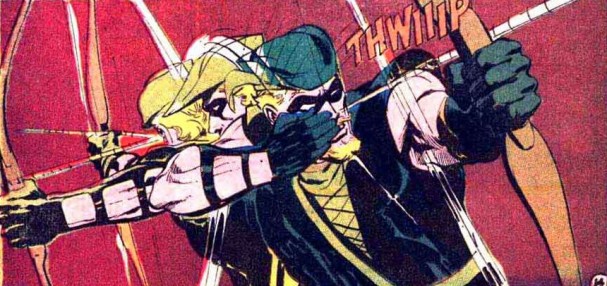

The catalyst for change came in several parts for the character. One major plot device in Justice League of America was his coupling with the recently widowed Earth-2 character of Black Canary, a love story that would last for decades. She was initially a “fish out of water”, while Oliver was becoming alienated from the rest of the League. Their mutual support would blossom into something more. Yet his change in character was more conclusively represented in a change in costume, and growing some facial hair. Beginning with Batman team-up book Brave and the Bold #85 (“The Senator’s Been Shot!”, September 1968), Oliver Queen got a new look for a new age from Neal Adams. In the DC Comics Year By Year: A Visual Chronicle (2010), the significance of the change is not underrated:

“Artist Neal Adams targeted the Emerald Archer for a radical redesign that ultimately evolved past the surface level…the most significant aspect of this issue was Adams’ depiction of Oliver Queen’s alter ego. He had rendered a modern-day Robin Hood, complete with goatee and moustache, plus threads that were more befitting an ace archer.”

His attitude shift was a decidedly anti-establishment one, and Bob Haney’s story highlighted Oliver’s internal struggle in this highly politicised issue. While both Batman and Green Arrow race to investigate the assassination of a Senator, their alter egos echo a sense of social responsibility that was highly topical in the late 1960s. Bruce Wayne, a friend of the senator, is sent to fill in his seat and help pass an anti-crime bill. Oliver is at a juncture in his life, trying to decide whether or not he should give up the (new) costume and focus on using his wealth to finance the construction of New Island, a second Gotham City.

His attitude shift was a decidedly anti-establishment one, and Bob Haney’s story highlighted Oliver’s internal struggle in this highly politicised issue. While both Batman and Green Arrow race to investigate the assassination of a Senator, their alter egos echo a sense of social responsibility that was highly topical in the late 1960s. Bruce Wayne, a friend of the senator, is sent to fill in his seat and help pass an anti-crime bill. Oliver is at a juncture in his life, trying to decide whether or not he should give up the (new) costume and focus on using his wealth to finance the construction of New Island, a second Gotham City.

The theme would be continued by O’Neil in Justice League of America #75 (“In Each Man There Is a Demon!”, November 1969), where Ollie literally fights his inner demons as they emerge in the form of a green spirit during a session with a psychiatrist. He begins to doubt himself, and is initially unable to take down a jewellery thief due to his own indecision. The matter was conclusively settled with the third major character development, when Oliver Queen lost his fortune to the machinations of “corporate fat cats”.

From this point forward, Oliver Queen/Green Arrow became a mouth-piece for the underprivileged and political left, a topic to be explored in more detail in the second part of this history. Faced with his new-found outlook on life, he did what all lost souls in the late 1960s did: he hit the road with a couple of friends…

In Part 2, we’ll unpluck the infamous Green Lantern/Green Arrow run from Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams, the arrival of Count Vertigo, Green Arrow lost in a wilderness of back-up stories and his television debut!

>>Proceed to Part 2>>

Agree or disagree? Got a comment? Start a conversation below, or take it with you on Behind the Panel’s Facebook and Twitter!

If you are an iTunes user, subscribe to our weekly podcast free here and please leave us feedback.

7 pings

Skip to comment form

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969) […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969) […]

[…] we left our favourite Emerald Archer in Part 1 of this retrospective, he was just beginning to find his voice. No longer content to sit on the […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969) […]

[…] Arrow arrived first, premiering all a approach behind in 1941. Though he was creatively small some-more than a Robin Hood-themed Batman knockoff, a impression […]