“A guy with a bow and arrow in the “shoot ’em up and leave ’em for dead” ’90s?” – Chuck Dixon

Green Arrow may have returned to the spotlight during the darker turns of the 1980s, but even he wouldn’t escape the superhero death toll of the 1990s.

Green Arrow may have returned to the spotlight during the darker turns of the 1980s, but even he wouldn’t escape the superhero death toll of the 1990s.

Mike Grell’s departure from the book coincided with a sea-change in the industry, with the Dark Age that arguably began with The Dark Knight Returns (1986) and culminated in the grunge and Gen-X leanings of Rob Liefeld. The black and white boom of the 1980s had made millionaires of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creators Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird by the early 1990s.

Imagine it: a world where comics sell in the millions. Often dismissed by “serious” comics readers, the early to mid-1990s was a period where comics were hot property. X-Men #1 (Marvel Comics, October 1991), created by Chris Claremont and Jim Lee, sold a standing record of 8.1 million copies across its variant covers, with X-Force #1 (Marvel Comics, August 1991), from Fabian Nicieza and Liefeld following just a few months later with another 5 million. They were riding the wave of an investment bubble, a collectors and speculators market that Comics Alliance rightly claims “almost ruined comics forever”.

Peaking in 1993, “the most successful year in comics industry history” (according to ComicChron), it was aided by the massive mainstream media publicity surrounding events like “Death of Superman”, and the black-bagged Superman #75 (DC Comics, January 1993) that shipped between 2.5 and 3 million copies. (By comparison, a top-seller today is anything over 100,000 issues, with the odd 300-400,000 issue sitting at the upper end of the scale).

The cynical Gen-X attitude saw a slew of younger heroes, and a new generation of legacy characters. Comic book artist Kyle Rayner replaced clean-cut military man Hal Jordan as the Green Lantern. Billionaire Bruce Wayne was briefly broken by Bane and the armoured Jean-Paul Valley used his killers instincts as the new Batman. Four different Supermen, including an angsty teen clone, vied for his throne during the Man of Steel’s absence. So, it comes with no surprise that even the fast-talking Oliver Queen couldn’t slip his way out of his own replacement.

In this fifth chapter of The History of Green Arrow, we witness Ollie travelling America following the departure of Grell, the discovery of a son, the death of Green Arrow and the beginning of a new era.

Also read:

-

- The History of Green Arrow Part 1 – From Golden Age to Golden Beard (1941 – 1969)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 2 – Hard Travelling Through the Wilderness Years (1970 to 1979)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 3 – Detectives and Dark Knights (1980 – 1986)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 4 – Longbow Hunting Through the Wonder Years (1987 – 1993)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 5 – At the Crossroads of Death with Connor Hawke (1994 – 2000)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 6 – Quiver through Brightest Day (2001 – 2011)

- The History of Green Arrow Part 7 – Losing the Beard: The New 52, ‘Arrow’ and the Contemporary Age (2011– )

At the Cross Roads (1993 – 1994)

Following Grell’s departure, DC wasted little time in bringing Green Arrow back to the rest of the superhero universe. During this interim era, a number of writers and artists were assigned to the title, mostly leading up to the “Zero Hour” event in 1994. Initially, Kevin Dooley took over for the “Cross Roads” arc, in which time Oliver Queen says goodbye to Seattle. Separated from Dinah/Black Canary following her discovery of his affair with the young Marianne (Green Arrow Vol. 2 #80, Nov 1993), Ollie’s road trip was perhaps meant to recall the classic Neal Adams/Dennis O’Neil run. Yet with C-list villains like Shrapnel, Rival (in a singular appearance), Deidre Dallas and a string of generic yakuza and ninja, many of these issues remain fairly forgettable in the wider history of Green Arrow.

Spanning San Francisco, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Dallas, New Orleans, New York, and of course Gotham City, writer Dooley was joined by Alan Grant (Green Arrow Vol. 2 #84 – #85) and Doug Moench (Green Arrow Vol. 2 #86, May 1994) to reintroduce Green Arrow to everyone from the Huntress to Catwoman and the Justice League. The transparent marketing tactic was purely a buffer zone before the “Zero Hour” tie-in issues, which did provide readers with a stirring conclusion in the final chapter. During “Cross Roads, Part Ten: He Who Hesitates…” (Green Arrow Vol. 2 #90, Sep 1994), time splits as he is chasing down a generic crook. In his own Sliding Doors moment, he manages to take down the thug in one version, but hesitates in the other and is shot and killed. Standing over his own dead body, he comes to the realisation that he cannot afford to waste a second in his line of work.

The “Zero Hour: Crisis in Time” mini-series itself proved to be a significant moment in the history of the archer. Written and illustrated by Dan Jurgens, it had the task of tying up the loose ends of inconsistent future continuities. In the grand tradition of Crisis on Infinite Earths, deaths occurred and it laid the groundwork for many changes. In a telling sign of the times, legacy character Kyle Rayner literally restrains the old guard of Hal Jordan, now driven mad by the Parallax entity and threatening to destroy the universe. Hal Jordan, his power now drained rendering him effectively impotent, is held by his literal successor as an arrow penetrates the circle on his chest. It’s almost a flipped version of the traditional Mars symbol used to represent men. Analysts can ponder the symbolism for a few moments.

Fittingly, it is his closest friend Oliver Queen that shoots the final arrow through his chest to end the madness. Having killed his best friend, Queen retreats to the same ashram he visited back in Flash #217 through #219 (September 1972 to January 1973) after accidentally killing someone (Green Arrow #0, “Cast Upon the Waters”, October 1994). Here the character of Connor Hawke, the young archer who would eventually be revealed as Ollie’s son, was introduced.

Legacy Era: Chuck Dixon and the Death of Green Arrow (1994 – 1995)

Eagle-eyed readers paying attention during that interim era may not have noted the author byline on “Cross Roads, Part Three: The Weight” (Green Arrow Vol. 2 #83, Feb 1994). Chuck Dixon, one of the most prolific comics writers of the 1990s with an average of 7 titles a month (and the creator of Batman’s Bane), would go on to define the latter part of Green Arrow’s first ongoing series, including the definitive run for Connor Hawke.

Dixon started out in the indies during the 1980s for the likes of Comico and First Comics, but it was his work on the Marvel Graphic Novel Punisher: Kingdom Gone (August 1990) that led to him working on the ongoing series The Punisher War Journal, for which he wrote around 30 issues. Yet it is his work at DC that he is most recognised for, beginning with a few mini-series (Robin, Cry of the Huntress, Joker’s Wild) and eventually becoming the key Batman writer of the 1990s, placing his stamp on a run that would last from the back-breaking Knightfall (1993-1994) to No Man’s Land (1999). A skilled writer and an excellent spinner of multiple plates, Dixon was still initially unsure about taking on the character. In the back-matter to his final issue (Green Arrow #137, October 1998), he wrote:

“I took on this character with some trepidation. I mean, a guy with a bow and arrow in the “shoot ’em up and leave ’em for dead” ’90s?”

The attitude would seem to typify the feeling towards many of the old-guard character during this era, and the coming months would see a seismic shift in the way the character was presented.

After being introduced in Zero Hour #0, as a fellow resident of the ashram, Hawke’s first adventures were actually by Kelley Puckett, with Dixon officially taking over from “The Truth Hurts” (Green Arrow #95, March 1995). The initial stories saw the duo on the road across America, even featuring a cameo from a not-so-dead Hal Jordan in the middle of the desert. The child of Sandra “Moonday” Hawke (and not Shado as many mistakenly believe), Connor is the antithesis of his father: innocent in the ways of the world, spiritual with an Eastern flair, sexually ambiguous and at the start of his career. His mixed Asian, African, and European heritage (something that hasn’t always been remembered by artists in later appearances) further sets him apart from the quintessential “angry white male” that Ollie became, clearly signalling change was in the air.

During this time, Ollie (under Dixon) further distanced himself from the old guard first by not wearing a costume at all, and next by changing it to a more stylised red and brown spandex number with a hood. It conclusively moved Green Arrow back into the world of superheroes that Grell had so carefully isolated him from. The real meat of the tale began with the five-part “Where Angels Fear to Tread” story arc, during which time Ollie and Connor team-up with the unlikely partner of Eddie Fyers, the mercenary operative who began as Ollie’s foe in The Longbow Hunters. Being the ’90s, eco-terrorists were the “villains” of the day, and Ollie finds himself on the wrong side of the moral high-ground when he joins Hyrax, the leader of the Eden Corp.

Following a confrontation with Hyrax, it’s revealed that she plans to destroy Metropolis with Mutajek 9-9, a weapon of mass destruction capable of levelling the city. Ollie finds himself strapped to the bomb as it heads towards the city. Appearing to him at this fateful moment as the Christ-like figure he was always been is Superman, now even sporting a messianic mullet to fit in with the edgier decade. He offers Ollie a choice: losing his arm or dying with the plane. In a death that stays true to form with the character, Ollie elects to die without losing the one thing that gave his life purpose. (An interest sidebar is that Frank Miller’s 1986 “Elseworlds” series The Dark Knight Returns features a one-armed Ollie, allegedly as a result of something Superman did. Conscious or not, it’s a Multiversity moment in the making).

Green Arrow #101 (“Run of the Arrow”, October 1995) opens with the explosion that kills our hero, leaving Connor Hawke pondering whether to take up his father’s mantle. A mere 8 years after Mike Grell’s The Longbow Hunters and subsequent series put Green Arrow in his first spotlight after half a century of backup stories, DC dispatched of what is arguably its social conscience. Like many of his contemporaries – including the aforementioned Superman, Batman, Green Lantern or even the Spider Clone saga over at Marvel – Green Arrow fell under a scrambling attempt to do something new with their line. Unlike the other characters, it took Oliver Queen a little longer than expected to make it back to his beloved Star City.

Green Arrow is Dead: Long live Connor Hawke (1996 – 2000)

Connor Hawke, along with Kyle Rayner, is perhaps the most prominent example of the “legacy” characters of the 1990s. In his first proper solo issue as the new Green Arrow, Connor Hawke is thrown immediately into the wider DC universe with a two-part “Underworld Unleashed” tie-in (Green Arrow #102-#103, November/December 1995).

A skilled archer, Hawke is perhaps more closely associated with his martial arts skills. Trained in the ashram, he can imitate the styles he observes. Indeed, towards the end of Dixon’s run (in the 5-part “Brotherhood of the Fist” crossover with his other books Nightwing, Robin and Detective Comics), Connor is established to be one of the finest martial artists in the DC Universe (Green Arrow #134 – #135, July/August 1998). He is a modern-day Caine from the 1970s Kung Fu TV series, programmed to appeal to a wider demographic than a hangover of 1960s rebellion.

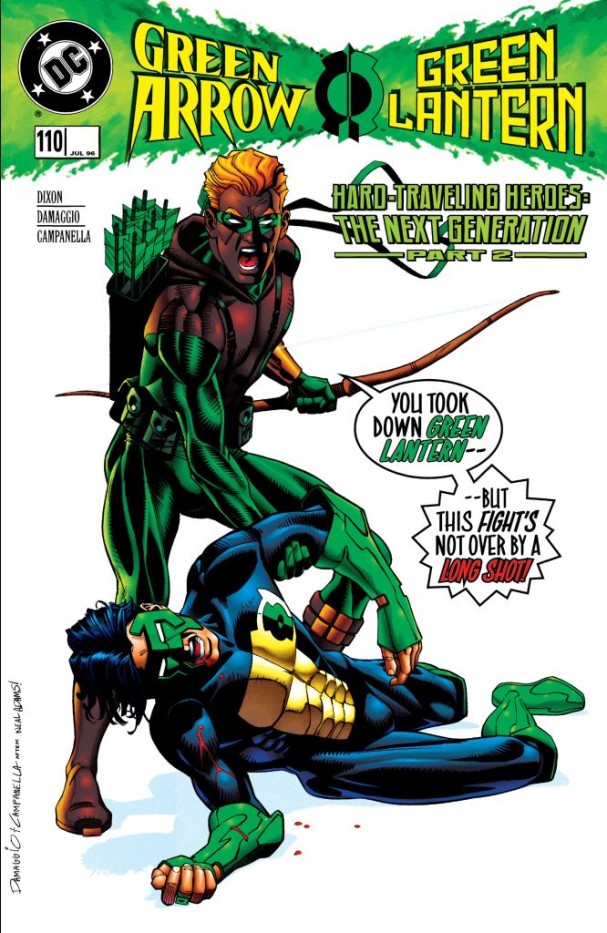

Yet for all of the attempts at “new” and “edgy”. Green Arrow couldn’t help but escape its own legacy. As early as Green Arrow #104, a friendship is established between Connor Hawke and Kyle Rayner, the new Green Lantern. Recalling the firm bond between Hal Jordan and Oliver Queen, a fully-fledged “Hard Traveling Heroes: The Next Generation” is launched with Green Lantern #76 (July 1996), following the same numbering as the previous volume. The Paul Pelletier cover is a direct homage to Neal Adams’ Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76 (April 1970), just as Rodolfo Damaggio’s cover art for Green Arrow #110 recalled Adams’ Green Lantern/Green Arrow #87 (December 1971). It was a concept that evidently worked, so much so that it was repeated in “Hate Crimes” (Green Arrow #125-#126 and Green Lantern #92, October/November 1997), again in “Three of a Kind” with the addition of The Flash (Green Lantern #92, The Flash #135 and Green Arrow #130-#131, March/April 1998)

While Connor Hawke would eventually develop a fan-base of his own, it is hard to view this legacy era as anything but a place-holder for the return of Oliver Queen. Hawke would make several appearances in other books during and after his own book was cancelled, including an inclusion in Grant Morrison’s revitalisation of JLA. Even here he couldn’t escape the past. In JLA #8-9, Connor helps the League fight The Key with his father’s trick arrows found in the Trophy Room. In the Green Arrow #1,000,000 issue (November 1998), which served as an epilogue to main series, the final panel confirmed it. A meditating Hawke comes to the realisation that “Oliver Queen is alive.”

In February 1998, about six months before Green Arrow went on hiatus, Newsarama announced that indie filmmaker Kevin Smith would be writing Green Arrow at some stage in the future. At this stage, he had not yet begun his now classic Daredevil: Guardian Devil run for Marvel. When Dixon’s series eventually ended with Green Arrow #137 (“Full Circle”, October 1998), editor Darren J. Vincenzo remarked in the “Sherwood Forum” back-matter:

“When I announced that Kevin Smith had agreed to come on board it was immediately decided that the best way to debut Kevin Smith’s GREEN ARROW was to relaunch the book. As I write this, Kevin is wrapping up the shooting of his latest film, Dogma. He’s already mapped out what he wants to do with his first story arc (which is, as I write this, planned to be a Prestige Format miniseries), and it will be under way by the time you read this.

“But, schedules being what they are, the relaunch cannot happen on the heels of this series.”

The prestige format idea (perhaps recalling The Longbow Hunters) would later be abandoned, and those deadlines seemingly kept slipping. By the following year, the book was still nowhere to be seen, leaving Green Arrow fans pondering the fate of their favourite archer. Chuck Dixon was one of those fans, telling Fanzing (Fanzing #20, September 1999):

“The delay is all I know about. I’ve honestly never read a Kevin Smith comic. I was waiting to read Green Arrow. I saw Clerks.”

Smith, who now had several comics works under his belt including Chasing Dogma (Oni Press, 1998-1999) and the aforementioned Daredevil run, continued to be asked about its status. Always ahead of the curb when it came to using his online fan-base to whip up enthusiasm for his projects (at the time, the movie Dogma), Smith spoke with fans via a CNN online chat about the future of the book in November 1999. Asked by a fan “will we see the comic published in 2000?”, Smith replied:

“I’m going to start writing “Green Arrow” very, very soon. I’m sure that DC will hold off on soliciting it until they have a good eight or nine issues in hand. Apparently, I have this reputation for lateness…”

That first issue would eventually arrive in February 2001.

Bonus: Other ‘Arrows’ (1994-2000)

While Connor Hawke continued to appear as the ‘default Green Arrow’ throughout the long hiatus between the Chuck Dixon and Kevin Smith runs, including a few cameos in the Devin Grayson/Rick Mays mini-series Arsenal (October 1998 – January 1999), following Ollie’s former ward Speedy, and alongside Eddie Fyers in Chuck Dixon’s Robin #79 (“Three Deaths for Arrakhat, Part 2: Something Fierce”, August 2000). Mike Grell even took a crack at Connor Hawke in an issue of The Batman Chronicles #5 (“Double Play”, Winter 1997) that he penned.

Even though Oliver Queen was dead during this period, DC still managed to keep the ghost (and potential audience interest) of the Emerald Archer alive through a series of retro-inspired stories. Two separate arcs featured in the Legends of the DC Universe series, the first yet another callback to the “Hard Traveling Heroes” era. “Peacemakers” (Legends of the DC Universe #7 – #9, August-October 1998) tells of the historic first meeting of Hal Jordan and Oliver Queen, with Green Arrow and Green Lantern unsurprisingly ending up on the opposite sides of an attempt to bring peace to a war ravaged nation. The second arc, “Critical Mass” (Legends of the DC Universe #12 – #13, January – February 1999) is a curious late Silver Age inspired piece that has a typical ‘super heroes have turned into destructive giants’ set-up. The heroes without powers, including Batman, Green Arrow and low-rent Jimmy Olsen wannabe Snapper Carr are on the case. This one can easily be placed in the early 1970s, with Ollie being coaxed out of his first ashram retirement. Similarly, “The Arrow and the Bat” (Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #127 – #131, March – August 2000) is a firm Brave and the Bold inspired piece, complete with Ollie in his original red gloves and beardless guise.

Yet other versions of Green Arrow kept popping up all over the place as well. There are the more obvious ones, including the “Elseworlds” tales of JLA: The Nail (August – November 1998), from Alan Davis and Mark Farmer, where Oliver Queen is a paraplegic after a battle with Amazo, and publicly decries the Justice League as aliens with an agenda against Earth. Similarly, there’s the beautiful Alex Ross art on an aged Oliver Queen in Kingdom Come (May – August 1996), which also features Red Arrow, an older Roy Harper/Speedy/Arsenal, who has copied Ollie’s classic costume in all but the colour. Then there’s the truly odd alternate Earth depictions.

At various times, the DC Universe is depicted as a Multiverse, filled with alternate versions of characters based on decisions and variations made by possible outcomes. Some of these are virtual mirrors, others get a little radical. Take for example Earth-D, appearing in Legends of the DC Universe: Crisis on Infinite Earths #1 (February 1999). It was an alternate Earth that existed prior to Crisis on Infinite Earth, and was very much like the DCU that we know, only more ethnically diverse. The Flash is Asian, and Superman is black. Green Arrow is a Native American archer (pictured above) and a member of the Justice Alliance of America. They team up with the Justice League of America to defeat the Anti-Monitor, but ultimately this Arrow (and his entire reality) are destroyed in a wave of anti-matter that destroys his home.

Interestingly enough, this version isn’t so far removed from the earliest origin stories of Oliver Queen. If you recall, way back in “The Birth of the Battling Bowmen” (More Fun Comics #89, March 1943), Green Arrow’s initial origin story saw him “grow up alongside Native Americans” where “Oliver Queen learned to appreciate the lifestyle of the people and gained some proficiency with a bow”. (This was, of course, later replaced by the more familiar island origin in Adventure Comics #250).

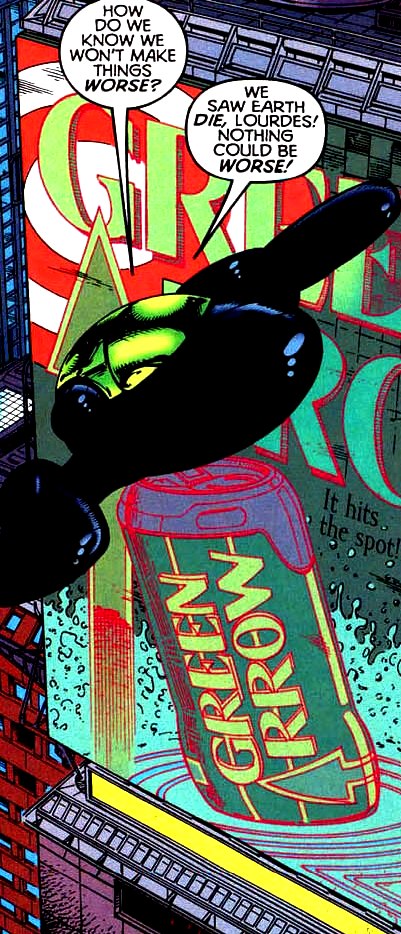

For the truly strange, take a visit to the Tangent Universe of Earth-9 where Green Arrow is, wait for it, a brand of soda (Tangent Comics: Doom Patrol #1, December 1997). With the slogan “It hits the spot”, at least he fared a little better than Doctor Light, who wound up as “Dr. Lite” brand cigarettes!

Beyond the Comics

Coupling the 1990s boom in comics sales was a corresponding rise in merchandise and tie-in properties. Despite not being the most popular hero in the playground, Green Arrow featured or appeared in a number of prominent pieces, some of which are now hot collectables.

The age of almost ubiquitous video gaming was upon us, and the mighty Sega Mega Drive (or Sega Genesis depending on which country you were in) was seeing its last kicks by 1994 as 32-bit systems came into popularity. Nevertheless, Justice League Task Force (Acclaim Entertainment) dropped in 1995 to little acclaim. Listed at No. 9 on Screw Attack‘s “Top Ten Worst Fighting Games”, a Grell-era hooded Green Arrow was one of the playable characters in this distant ancestor of 2013’s Injustice: Gods Among Us. Here’s a bit of Green Arrow not faring terribly well against Batman:

While not quite as varied as the products of the 1970s, a number of figures and games came out during the mid-to-late 1990s. Connor Hawke featured sparingly in the merchandise, perhaps indicative of his lower popularity. Nevertheless, several variants were released of a Green Arrow Total Justice Figure (Kenner Toys) featuring Connor between 1997 and 1999 (with later editions store exclusives). Coming with a “Multi-Action Mega Longbow”, the 5-inch figure came with the same “FRACTAL TECHGEAR battle accessories” that all figures in the line were packaged with. Once one of the rarer items from the third wave of these action figures, it is now fairly easy to track down on auction sites such as eBay. Connor Hawke also featured on several OverPower Cards, a collectible card game that rode the wave of Magic: The Gathering‘s debut in 1993.

Yet it was Oliver Queen who still transcended the boundaries of death to live again in cloth and plastic. As the “legacy” characters gave way to a retro revival in the late 1990s/early 2000s, we started to see items like the 1999 DC Super Heroes Silver Age Collection Green Arrow 9-inch figure, wearing a cloth costume that recalled the Mego toys of the 1970s. A Silver Age Green Arrow even made it as one of the token pieces in the 1999 Justice League of America Monopoly!

Yet it was Oliver Queen who still transcended the boundaries of death to live again in cloth and plastic. As the “legacy” characters gave way to a retro revival in the late 1990s/early 2000s, we started to see items like the 1999 DC Super Heroes Silver Age Collection Green Arrow 9-inch figure, wearing a cloth costume that recalled the Mego toys of the 1970s. A Silver Age Green Arrow even made it as one of the token pieces in the 1999 Justice League of America Monopoly!

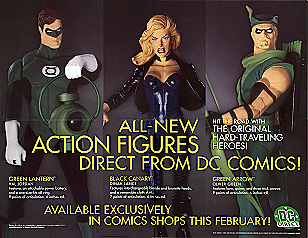

Of course, the Neal Adams inspired items still remained the most popular. At the dawn of the millennium, the retro revival was hitting its stride, and the “Hard Traveling Heroes” love was once again mined. Three action figures from DC Direct were sold under the “Hard Traveling Heroes” banner, with Ollie, Hal and even Dinah getting their own figures for this run. There was also a seriously cool Green Arrow Import Resin Kit Model that came out in 2000 and is now incredibly hard to come by.

In Part 6, we’ll look at the return of a hero under the guidance of Kevin Smith, and how Brad Meltzer and Judd Winick helped revive his status as a central figure at the heart of the DC Universe.

>>Proceed to Part 6>>

Agree or disagree? Got a comment or correction? Start a conversation below, or take it with you on Behind the Panel’s Facebook and Twitter!

If you are an iTunes user, subscribe to our weekly podcast free here and please leave us feedback.

5 pings

[…] >>Part 5 – Coming Soon>> […]

[…] discussed in the previous chapter of this series, editor Darren Vincenzo fully intended Ollie’s return in a rebooted series, commencing with a […]

[…] Ross, and more recently in Mark Millar and Frank Quitely’s Jupiter’s Legacy. Indeed, DC spent much of the 1990s handing the keys to dad’s car over to Kyle Rayners, Connor Hawkes, and Wally Wests of the […]

[…] The History of Green Arrow Part 5 – At the Crossroads of Death with Connor Hawke (1994 – 2000) […]

[…] an interesting choice of eras in the history of Green Arrow, coming at a literal crossroads for the character and the publisher. Mike Grell had just left the book, and after 80 issues of a […]